stress and me – Part 1 of 3

My research on stress in the events industry

In order to explain why I have dealt with the subject of stress, I have to start with Ekke. Ekke was a decorator and musician. He was huge, had long hair and was almost always in a funny mood. And every time he called me "mouse", I knew that he had forgotten my name again. I really liked Ekke. That's why it was quite a shock when he died suddenly in 2016. It's not known exactly what caused Ekke's death, but a heart attack is suspected. Ekke had just turned 50.

A short time later, my colleague Jörg, a sound engineer, died of a heart attack, Jörg was 50. I started to think about why they died of heart attacks so suddenly, far too early and so unexpectedly. After that, my own life went haywire and I was diagnosed with severe depression. Then came corona and with corona came more deaths. Not corona deaths, but heart attacks. Martin, lighting technician, died at 52 and Woody, tour manager, at 56. That was the time when I was looking for a topic for my Master's thesis and it was clear to me that I had to investigate this in more detail. There are countless studies on the fact that doctors have an incredible amount of stress and become ill as a result. But there are absolutely no scientific studies on us in the events industry. So I started to look for them. I found a British poll by POINT3 and AEO from 2019, in which 70% of the participants from the events industry stated, their stress levels were at least 7 out of 10. The Career Cast Job Barometer found the job of "event coordinator" to be the fifth most stressful job in the world. And that for six consecutive years (2016-2021). And that was all before the coronavirus pandemic. Whether you believe in it or not, are vaccinated or not, sick or not, I was firmly convinced that the pandemic has really increased the stress levels of all of us for a variety of reasons.

So I posed the following question:

- Is there a link between the events industry, increased stress levels, and an increased incidence of stress-related illness?

|

To answer this question, I have taken various steps:

- Found out what stress actually is

- Established the current state of research on stress-related diseases

- Started a survey in which the following factors were analysed:

- What stressors do we have in the events industry?

- Do we have higher stress levels?

- Do we have more stress-related illnesses in the events industry?

- The following points were clarified using the available data:

- Are stress and stress levels related?

- Are stress levels and stress-related diseases related?

In this first part of my report, I would like to explain what stress is and how it leads to illness.

What is stress?

In 1997, Cohen et al. defined stress as a process in which stressors or stimuli tax or exceed an organism's capacity to adapt. I find two things interesting about this definition. Firstly, a distinction is made between taxing and overtaxing. Being taxed is a so-called adaptive reaction, which means that our organism is able to cope with this demand. Being overtaxed, on the other hand, is a maladaptive reaction, i.e. one that our organism can no longer cope with. As early as 1976, Selye introduced the terms eustress for demanding stress and distress for overwhelming stress. Colloquially, the terms good and bad stress are also used. On the other hand, this definition includes the two main factors for stress, namely the stressor, i.e. the external stimulus, and the adaptability or resilience of the organism. It becomes clear that a stress reaction not only requires a stressor, it also requires an overstressed person. And that is the crux of the matter with stress: not everyone reacts to every stressor in the same way.

Let me try to explain this using a few examples:

The swimming pool:

Suppose someone were to push you into a swimming pool. The person pushing you is our stressor and you are the organism. There are different types of reactions that you can choose from and which one you choose (unconsciously, of course) depends very much on whether you are overwhelmed.

Are you able to swim? Then you will most likely be a little surprised, maybe even annoyed or you will have fun.

You can't swim? Then you'll most likely get stressed because you're in a potentially life-threatening situation that you can't control.

The snake:

There are stressors that are very universal. These include high altitudes, earthquakes, explosions, etc. These are stressors that should actually stress everyone because they are life-threatening in a very real way. But there are also people who don't react to certain stressors with stress. For example, I find snakes totally fascinating, which is why I often get very close to them and even follow them when they flee. This is quite unnatural and admittedly also stupid.

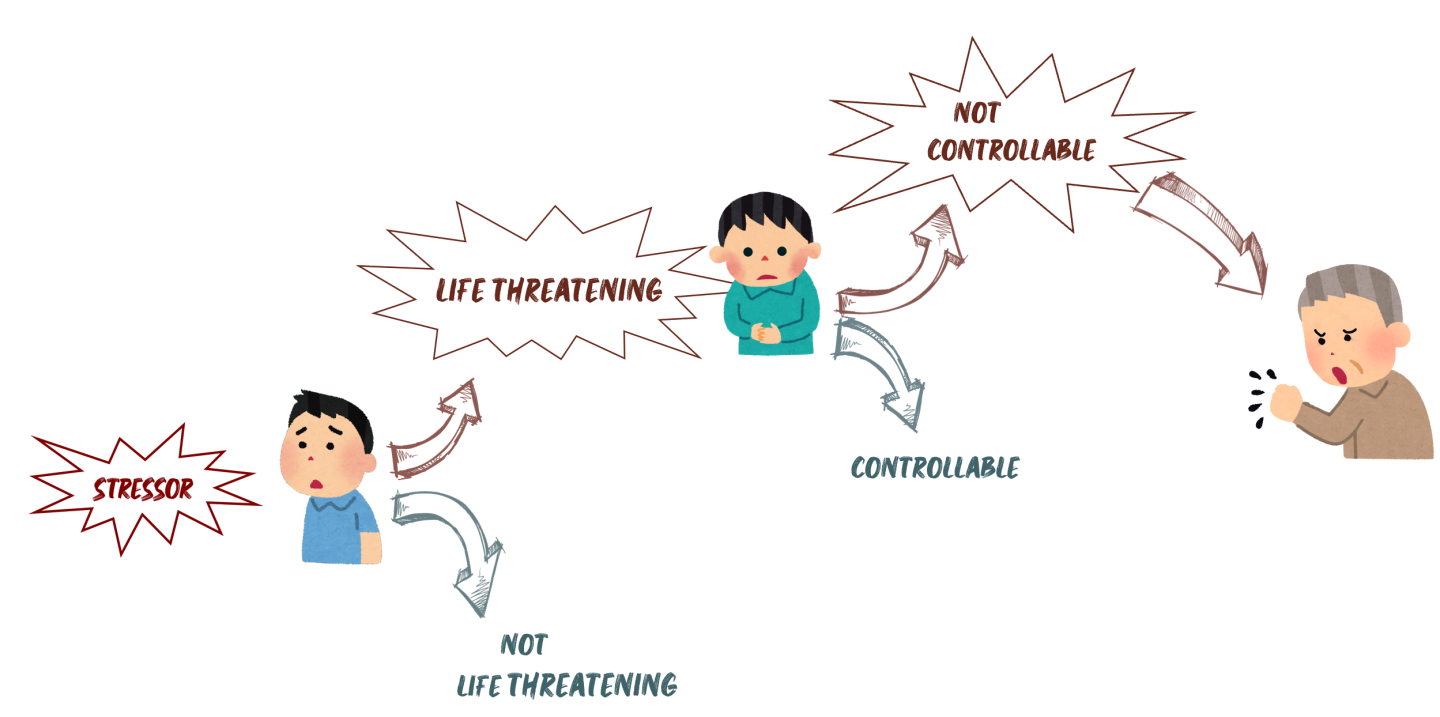

In these two examples, it has become clear that the reason why we feel stress depends largely on whether we perceive a situation as life-threatening - regardless of whether it actually is life-threatening - and on whether we can control it.

This stress flowchart shows the two factors for stress. The organism that is confronted with a stressor categorises it as either life-threatening or not life-threatening. If it is categorised as life-threatening, the organism makes a further decision, namely whether the stressor is controllable or not.

|

If the decision is made that a stressor is life-threatening and cannot be controlled, the organism goes into the flight-or-flight mode, Kohlhaas et. al 2011 claim.

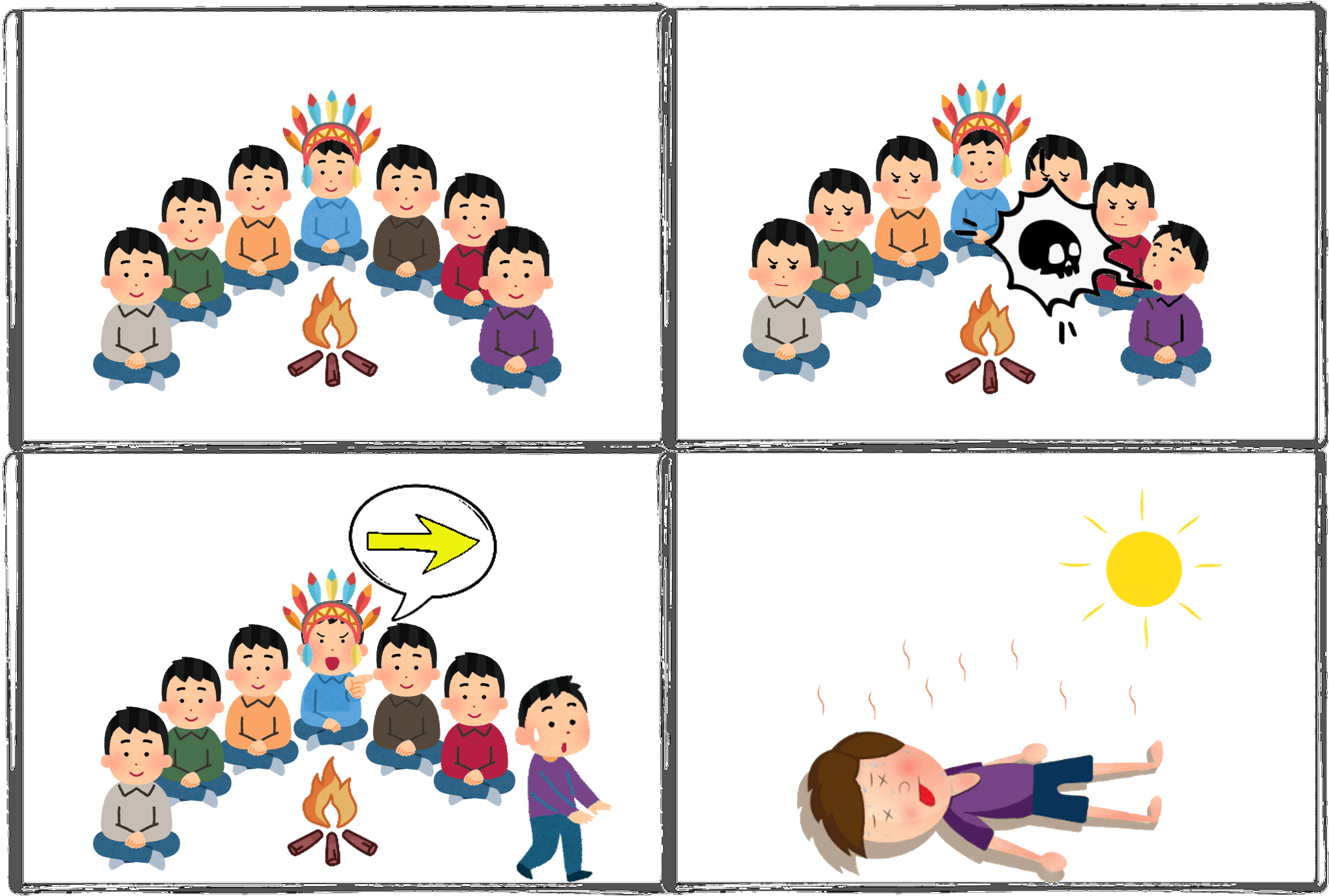

A side note: Nowadays, most of the stress factors we react to are no longer life-threatening (e.g. time pressure). To understand why we still react with stress, we need to understand the principle of rejection:

When we were hunter-gatherers, we relied on living in groups because we could not survive on our own. In order to live together, there were rules and someone who was responsible for ensuring that these rules were adhered to.

If someone broke the rules, they were excluded from the tribe. Back then, this almost certainly led to death. And then evolution ensured that the people who adapted reproduced, whereas those who were excluded from the tribe (and probably dead) could no longer reproduce.

|

So the need to conform to the rules or the boss has grown in us over generations. "This urge is so fundamental to us that it can trigger fight-and-flight mode when we feel bullied, rejected or shamed by our social group," says Harperwest in her article on the phenomenon. In their 2008 study, K. Ochsner and his colleagues also speak of social death, which at the time was also a physical death.

In other words, the fight-or-flight mode. You've probably heard this before, but what is it anyway?

Let me try to explain it in more general terms:

In our brain, the cerebral cortex is responsible for categorising whether a situation is life-threatening and controllable. This does not usually happen consciously, so we are not aware of it.

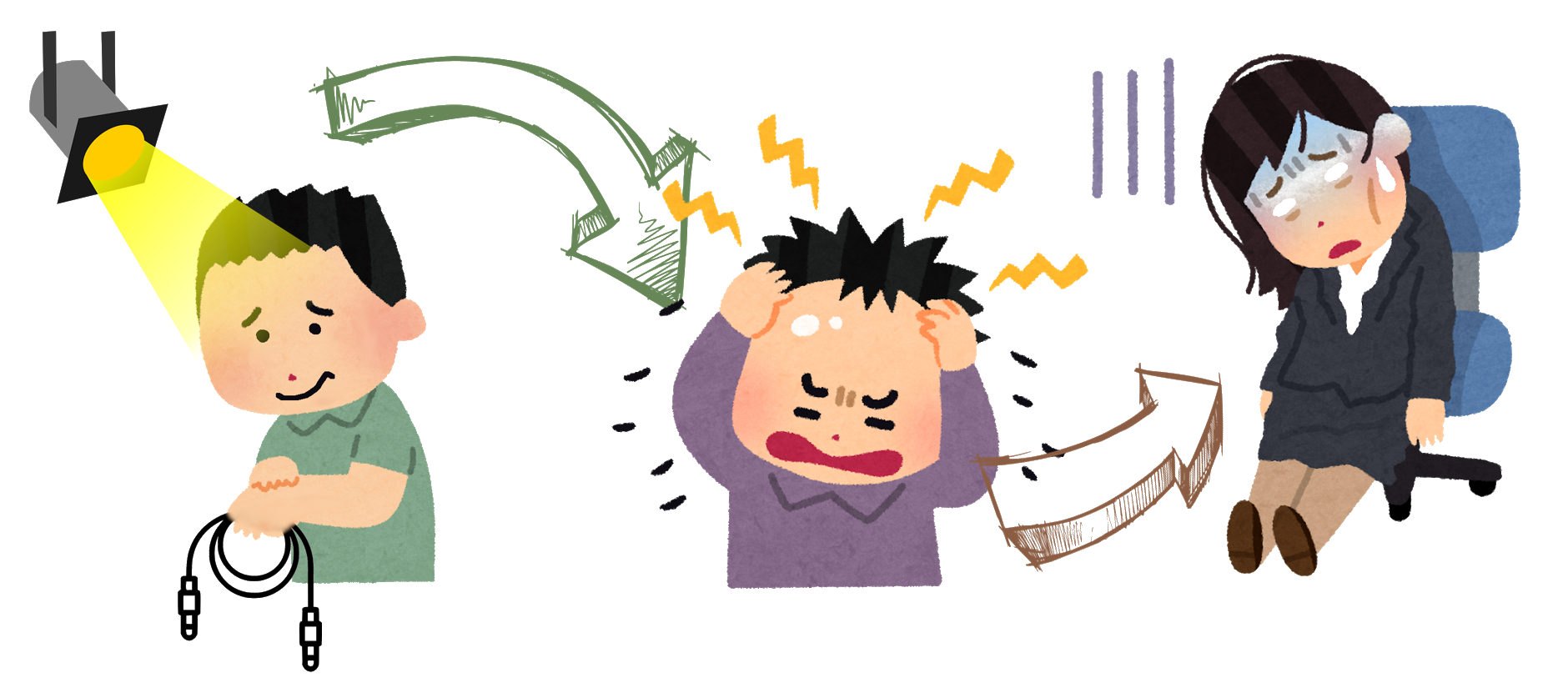

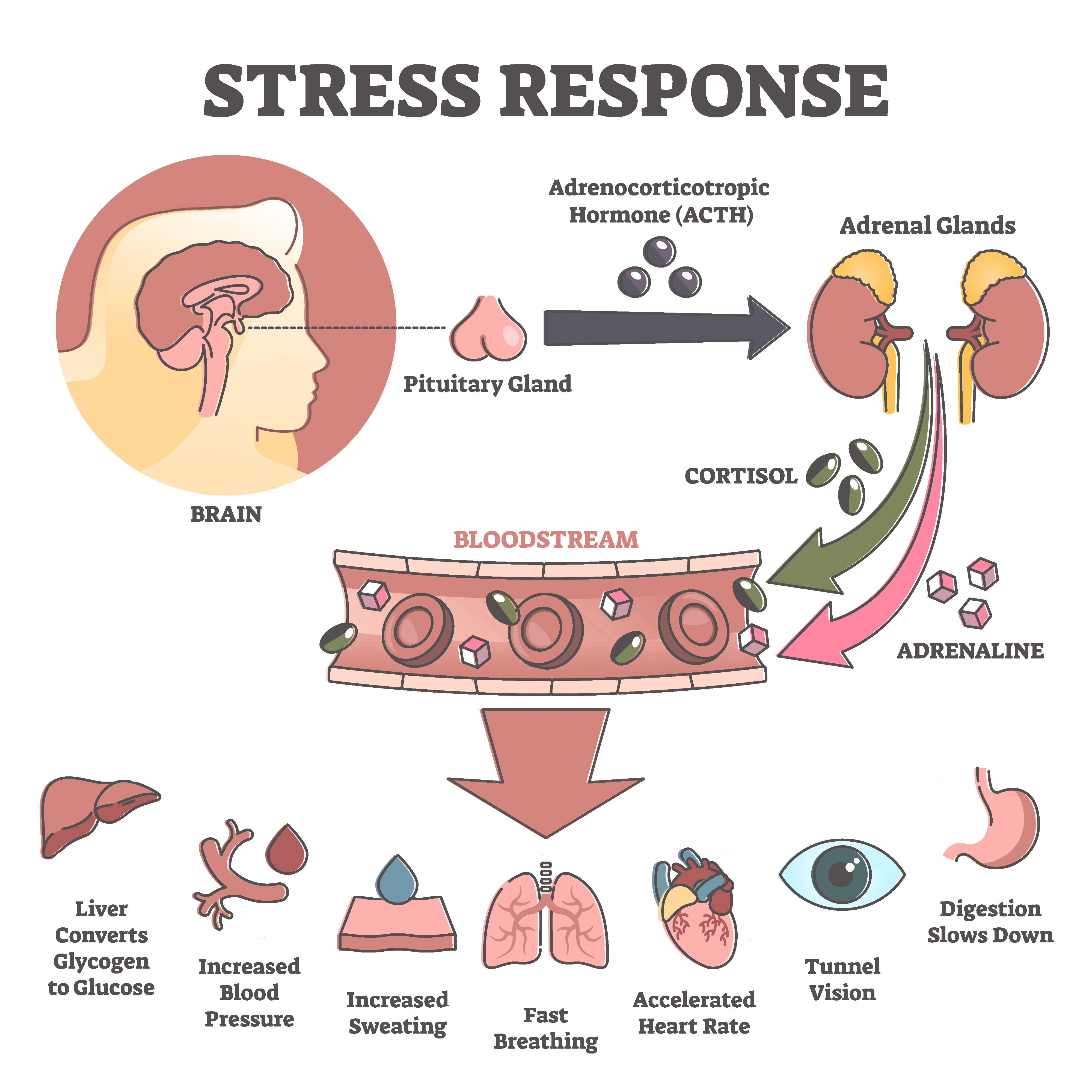

What we do realise, however, is what happens next. The so-called HPA axis is activated. HPA stands for Hypotalamic-Pituary-Adrenal, i.e. the connection between the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland (two parts of the brain) and the adrenal gland. The cerebral cortex sends neurotransmitters via the pituitary gland and the amygdala - other regions of the brain - to the adrenal gland, which then produces adrenaline. You know the feeling: the heart beats fast, breathing quickens, blood pressure rises - all of this ensures that energy is made available in the body, which we need when we are faced with a real threat - according to Dallman & Hellhammer, 2011 and Mariotti, 2017.

|

The situation only becomes problematic if the stressor persists over a longer period of time. This is when the cerebral cortex sends hormones to the adrenal gland via the pituitary gland, which then produces cortisol. Cortisol keeps our blood pressure high and our attention sharpened. Cortisol also influences the inflammatory processes in our bodies and regulates the release of hormones, including the hormone cortisol itself. After a while, the body becomes resistant to cortisol and loses its balance (Mariotti, 2017; Segerstrom & Miller, 2004; Dhabhar, 2011).

What are stress-related diseases?

This constantly elevated cortisol level and the imbalance in the hormone balance as well as inflammatory processes in the body cause a whole range of diseases. This includes, for example, all types of cancer (Baum et al., 2011), an increased risk of infectious diseases such as HIV (Fischer-Pedersen et al., 2011; Perez et al., 2011), reduced reproductive capacity, chronic pain, eating disorders, Alzheimer's disease, sleep and memory disorders, stomach ulcers, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and drug addiction (Davis et al., 2011; O’Connor & Conner, 2011; Hash-Converse & Kusnecov, 2011; Brooks et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2017; Grunberg et al., 2011; Digestive Health Team, 2022).

However, there are two diseases in particular that have been linked to stress by countless research findings: Cardiovascular disease (a.k.a. heart attack) and depression.

- Stress is an important risk factor for cardiovascular diseases such as heart attacks, strokes and high blood pressure (Crestani, 2016; Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009). Stress also leads to the promotion of stress- and disease-promoting lifestyle habits. This can be smoking or alcohol consumption. Studies have shown that smokers smoke more under stress. This further increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. The study also showed that people under stress do stress-regulating activities such as sport less frequently and tend to eat less well. Elevated cortisol levels also make it more difficult for overweight people to lose the weight again and obesity is another risk factor for cardiovascular disease (Bekkouche et al., 2011). As you can see, this creates an unpleasant vicious circle that eventually fuels itself.

- There is also overwhelming scientific evidence on the link between depression and stress (Tennant, 2002). According to a study by Kendler in 1999, for example, depressed patients regularly show increased cortisol levels and structural changes in the HPA axis. The same study also recognises that one month after a stressful event in a person's life, the likelihood of experiencing a major depressive episode is five times higher than in other phases.

And that brings me back to the beginning of my story, because when I found this out, I realised that Ekke's, Jörg's, Martin's and Woody's heart attacks, as well as my own depression, were not necessarily coincidental. But to prove this, I first had to start a survey. And that's what Part 2 of my report will be about.